The oceans are the biggest, wildest, least understood part of the planet. But we’re getting to know them better every day, thanks to new technologies that are fathoming the depths in new and inventive ways

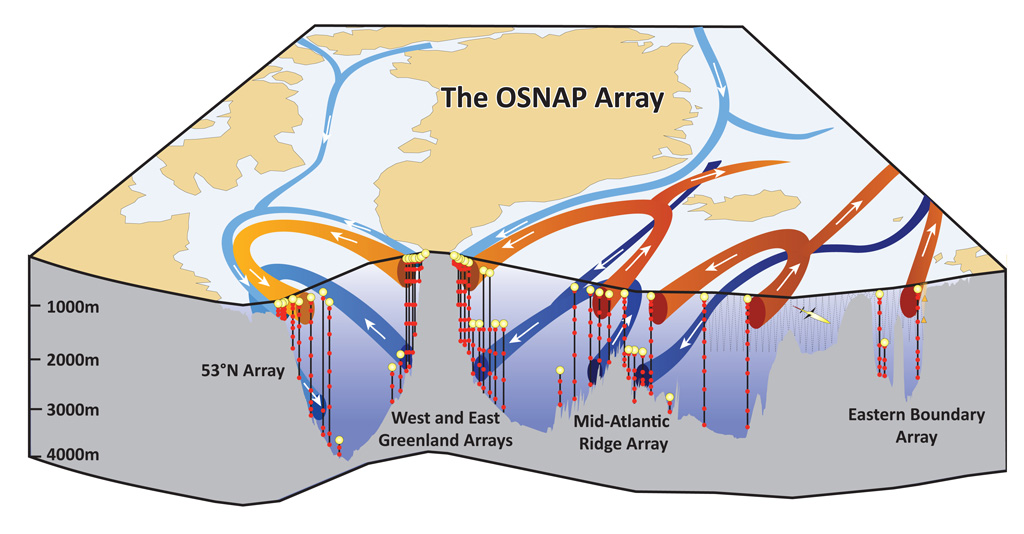

Between Scotland, Greenland and Canada, an array of 58 underwater sensors stretches along 3,000 km line. Each sensor consists of a giant, air-filled ball that sits near the ocean surface.

The ball is fixed to the seafloor thousands of metres below via a mooring line and along the line’s length are various instruments that measure water temperature and salinity, as well as the speed and direction of currents flowing past.

The aim of all these sensors is to monitor the Atlantic’s subpolar gyre, which is a massive current of warm water that swirls anticlockwise across the North Atlantic.

The gyre releases heat to the atmosphere, which flows over the UK and Europe. “That’s what keeps us warm,” says Prof Penny Holliday, UK principal investigator of OSNAP, the programme behind the senor array.

“We can see this effect by comparing temperatures of the UK or Europe with the same latitude in Canada. The difference is caused by the heat brought to us by that large-scale ocean circulation.”

The gyre plays a key part in climate models, distributing heat and carbon around the planet, but until the array was installed, scientists had no idea how strong the circulation was or how it changed over time.

It’s important for the way we interpret climate models and the predictions we make about changing climate

Prof Penny Holliday from the UK’s National Oceanography Centre and UK principal investigator of the Overturning of the Subpolar North Atlantic Programme (OSNAP)

The OSNAP array will stay in place until at least 2024, to continue monitoring the gyre and boost the confidence of future climate change predictions. Holliday’s team are also bolting on new devices to measure oxygen levels.

“One of the big questions in the world at the moment is an issue of whether the ocean and some shelf seas are losing oxygen,” she says. “We’re able to build on this array that was designed for another purpose to get extra information, which is really exciting.”