Banned chemicals may still be threatening the fertility of male porpoises off the UK

Industrial chemicals in the ocean have long been linked with health threats to whales and dolphins, but until now research has mostly focused on mothers and their young.

In a new study, scientists at the Institute of Zoology at the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) studied male cetaceans and found high levels of PCBs together with smaller testicles in some otherwise healthy animals.

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/84/d6/84d60fbf-afa1-4d98-9c43-a9f61ac2f58f/bottlenosed_dolphins.jpg?w=1110&ssl=1)

Populations of harbour porpoises off the UK have pregnancy rates less than half of pods living in less contaminated waters. This may be a result of an impact on both male and female fertility.

This is the first time that we have investigated and found that PCBs have a negative effect on male fertility. That’s really important because it means that current risk assessments might be underestimating the threat to our marine mammals

Rosie Williams – ZSL lead researcher

Populations of harbour porpoises around the UK are believed to be stable, though the animals face threats from pollution, accidental fishing and infection. The situation is much more dire for killer whales, which are down to a handful of individuals.

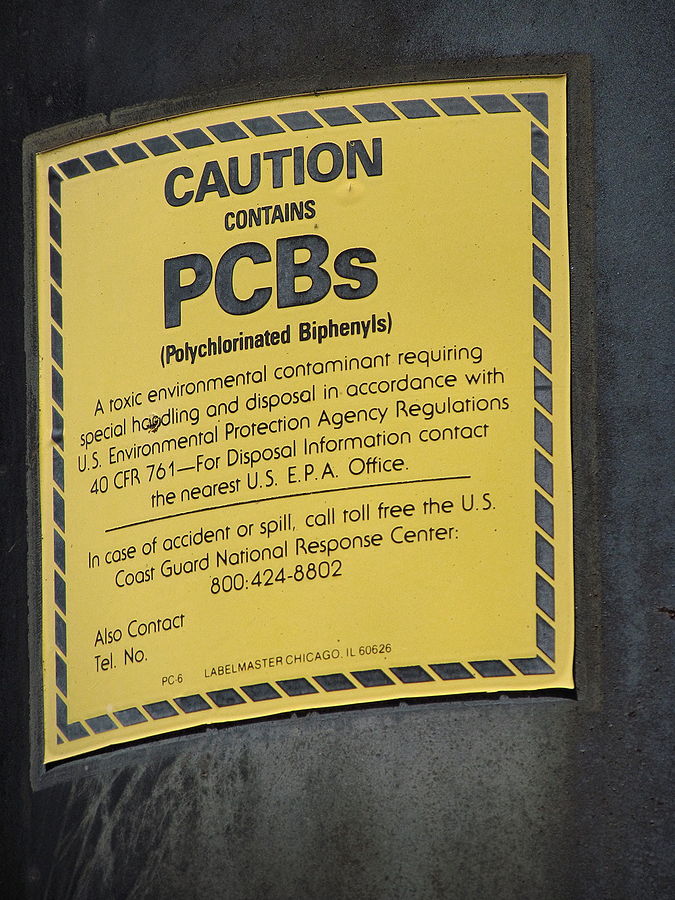

What are PCBs?

Because of their non-flammability, Polychlorinated byphenyls (PCBs) were widely used for decades. They went into everything from plastics and paints to electrical equipment until they were banned in the late 1970s over concerns about toxicity.

PCBs have since been demonstrated to cause cancer in animals as well effects on the immune system, reproductive system, nervous system and other serious problems.

PCBs don’t readily break down once in the environment, they can remain for long periods cycling between air, water and soil. PCBs are still entering the oceans, particularly from landfill sites where they can escape into waterways and on into the sea.

PCBs in the ocean

Once in the ocean PCBs build up can in the marine food chain, affecting dolphins and porpoises in a process known as bioaccumulation. One orca, nicknamed ‘Lulu’, was found dead off Scotland in 2016 with the highest levels of PCBs ever recorded.

PCBs have been linked with a number of risks to whales and dolphins, particularly in the early stages of life. A recent study found dolphins living in the English Channel were exposed to a “cocktail of pollutants”, which are passed down from mother to calf.

Scientists think PCB exposure at high levels can cause a number of effects on the animals’ immune system, reproductive system and brain. In humans, researchers have found a correlation between high PCB exposure and changes in sperm quality.

There are particular concerns for predators at the top of the food chain, such as killer whales and bottlenose dolphins, which accumulate the highest levels of PCBs in their blubber.

The study, carried out in collaboration with experts at the Scottish Marine Stranding Scheme, Brunel University, Exeter University and the Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (Cefas), is published in the journal, Environment International.